Distant or nearby, traversed in reality or simply fantasised: in the nineteenth century, foreign lands allowed French music to question its identity.

With the Industrial Revolution, what was far away was brought closer at the speed of a steam engine: the dreamed-of Orient of fairy tales and explorers lay within the reach of well-off Europeans. For the less wealthy, the drawings in illustrated newspapers opened windows onto other lands. The musical output of nineteenth-century France echoed this fascination: the plots of its operas were generally set beyond the nation’s borders, and dances imported from abroad nourished a large part of the instrumental repertory. In parallel to the bellicose, colonialist geopolitics of the age, artists also journeyed to foreign climes in order to seek new paths. Travel took on the sense of a quest for origins, bringing with it the hope of regenerating an exhausted West.

Translation

‘The scene is set in France, in the present day’: now there’s a phrase that virtually never appeared at the head of a nineteenth-century French opera libretto. Even when one might wager that the plot was inspired by the most immediate current events in Paris, its setting was shifted: transposed into the past – ancient, medieval, historical or legendary – or transported to more or less exotic lands where, nonetheless, everyone spoke perfect French. To understand this usage, we should probably bear in mind, in the first place, that Romantic opera was an art under close surveillance. And censorship (or self-censorship) was exerted not only over political statements in the works in question, but also over the morals portrayed therein. For example, the fatal passion of Don José in Carmen was acceptable to French spectators of 1875 when it blossomed in Spain half a century earlier. It would have been intolerable if this character had been a contemporary and compatriot of theirs. We must therefore consider that these dramas tell first and foremost the story of the time and place in which they were created, even before depicting an exotic reality. In the mirror of these distant worlds, the French could see themselves as they were, without actually having to acknowledge the fact.

‘The scene is set in the capital of the Thirty-Six Kingdoms.’

L’Étoile, Leterrier & Vanloo / Chabrier, 1877

Fascination

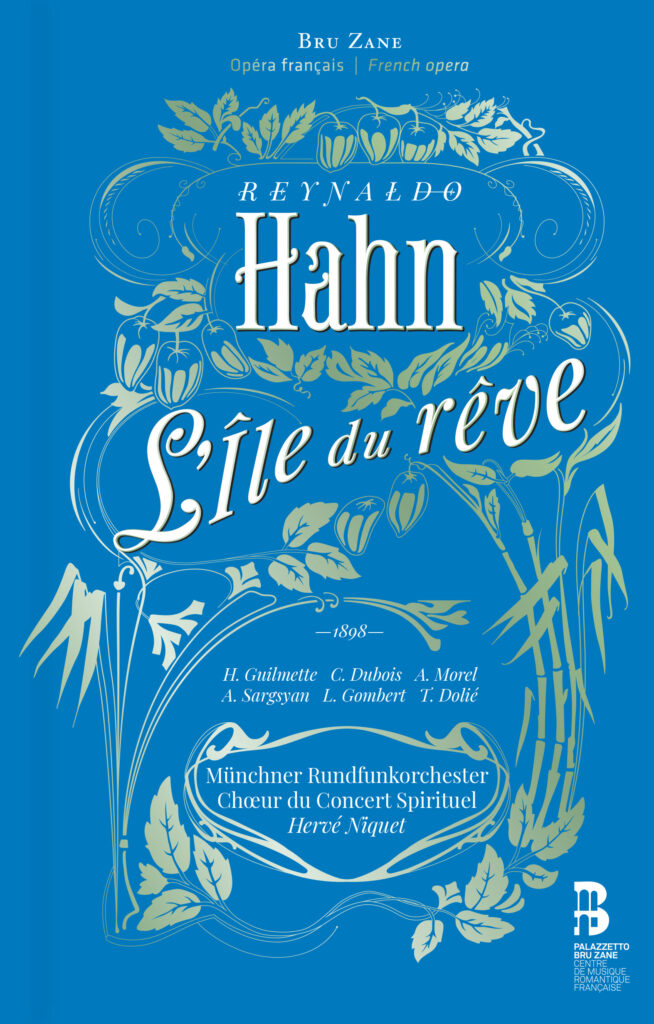

This art of transposition also benefited from a fascination with different and older worlds, which spread more widely through society from the Romantic era onwards. At the same time as colonial empires were built up, great explorers were glorified – such as Vasco da Gama in Bizet’s eponymous ode-symphonie of 1860 and Meyerbeer’s last opera L’Africaine (1865) – and composers vied with one another to set tales of adventures around the globe. Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1717) enjoyed a belated vogue in France and was adapted for the stage by Offenbach in 1867. Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s Paul et Virginie (1788) inspired operas by Kreutzer in 1791 and Le Sueur in 1794 before achieving success in Victor Massé’s version (1876). Pierre Loti’s novels inspired a stream of works in the Paris opera houses from the 1880s (Delibes’s Lakmé) to the turn of the century, with music by André Messager (Madame Chrysanthème), Lucien Lambert (Le Spahi) and Reynaldo Hahn (L’Île du rêve). Like the pictures published in the illustrated journals of the time, operatic sets and costumes too responded to this popular curiosity: they offered the possibility of seeing foreign countries without undertaking a sea voyage.

Eroticisation

Another factor that lay at the heart of the dream of ‘the Orient’ – which also embraced Spain and the Levant, by way of North Africa – was the search for a sensuality that rigid morality condemned in Western Europe. While it was taboo in other circumstances, female desire could be frankly expressed in an opera set in Cairo, Japan, Turkey or India. In Marguerite Olagnier’s ‘Arabian tale’ Le Saïs (1881), the metaphors are utterly transparent: ‘The languid flowers opened their calyces to the love-struck bees.’ This sexual ‘liberation’ of foreign women, mostly viewed through the male imagination, was anything but progressive. Authors and audiences fantasised about such women in the same way as they liked to imagine land marked out for colonisation: docile and fertile, awaiting the arrival of Western man to come to full bloom. Nonetheless, this dramaturgical zone situated beyond bourgeois propriety made it possible to tackle themes that were rarely dealt with openly in other contexts: passionate love between characters of different skin colours could be explored if care was taken to transpose their story into the past (Offenbach’s La Créole, 1875) or some faraway setting (Lakmé or L’Île du rêve).

‘Our two modes, the major and the minor, have been so exhaustively exploited that we should welcome every element of expression capable of rejuvenating the language of music.’

L.-A. Bourgault-Ducoudray, 1878

Appropriation

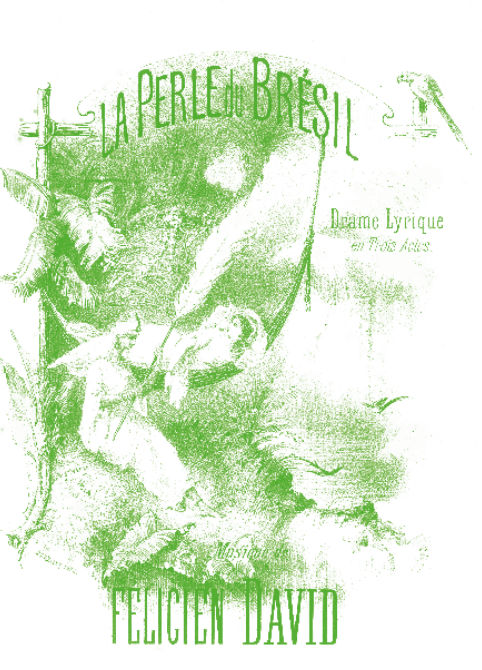

In musical terms, Romantic exoticism did not venture into the realm of ethnographic revelation. There were very few composers – Félicien David, Camille Saint-Saëns, Ernest Reyer and Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray among them – who travelled the world and brought back, in their notebooks, melodies or rhythms that tinged their scores with a more or less authentic ‘local colour’. At first, musical orientalism relied on a slight modal coloration of the melodic lines, while wholly tonal harmonies kept them within the ordinary realm of Western music. Nevertheless, as the Third Republic advanced, music from outside Europe did inspire a number of artists to find new ways of distancing themselves from the waning star of Romanticism. In addition, folk music from countries closer to France, such as Spain and Italy, had been a favourite resource of French composers since the early nineteenth century. It enabled them to avoid straying too far from the tonal system, while at the same time clearly marking a geographical divide. As a result, frequently used topoi such as boleros and canzoni tended to be assimilated into French art music.

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay