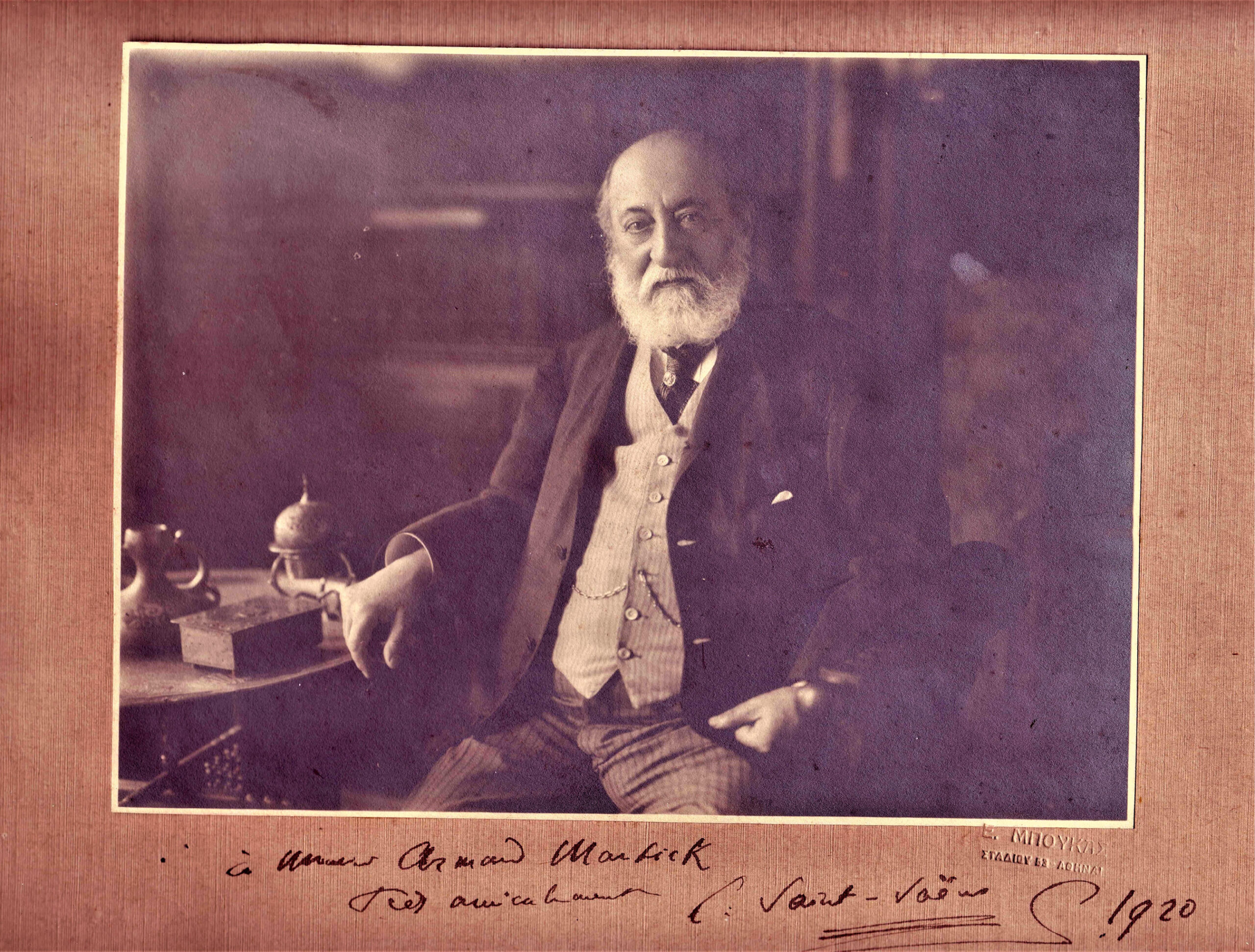

A century after his death, Saint-Saëns is still what one might call an ‘unknown celebrity’: though a few of his works have travelled all over the world, many more have sunk into oblivion. Focus on a chameleon-like, globetrotting artist.

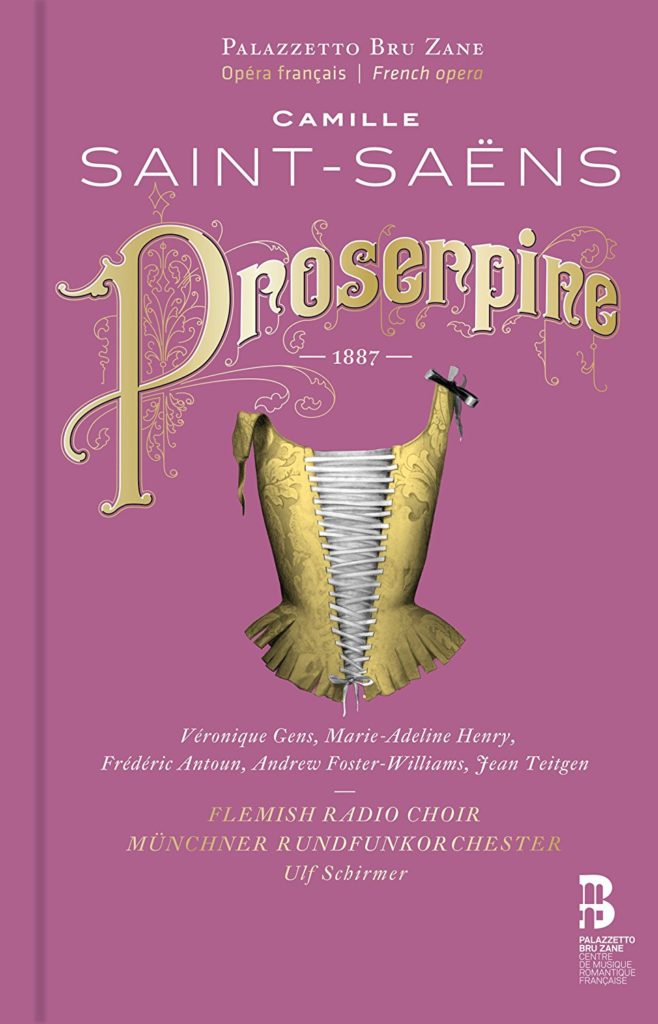

The history of music has granted a special place to certain works by Camille Saint-Saëns. Indeed, the international fame of Le Carnaval des animaux, the First Cello Concerto, Danse macabre, the Second Piano Concerto, the ‘Organ’ Symphony and Samson et Dalila sets him above Gounod and Massenet in the ranking of posterity. Yet, when one examines his vast catalogue of works, many treasures seem neglected by our concert halls: who is familiar with his string quartets and Piano Quintet? His oratorio in English The Promised Land? His operas Phryné, Frédégonde and Déjanire? After publishing a selection of his correspondence and a book on his travels in the Orient, the Palazzetto Bru Zane has already recorded his cantatas for the Prix de Rome and his operas Les Barbares, Proserpine and Le Timbre d’Argent. Several discs of mélodies – including one with orchestra – have also revealed a subtle and constantly renewed musical style. It therefore seemed only natural for the Centre de musique romantique française to continue its work on this artist by devoting a cycle to him to mark the centenary of his death.

The history of music has granted a special place to certain works by Camille Saint-Saëns. Indeed, the international fame of Le Carnaval des animaux, the First Cello Concerto, Danse macabre, the Second Piano Concerto, the ‘Organ’ Symphony and Samson et Dalila sets him above Gounod and Massenet in the ranking of posterity. Yet, when one examines his vast catalogue of works, many treasures seem neglected by our concert halls: who is familiar with his string quartets and Piano Quintet? His oratorio in English The Promised Land? His operas Phryné, Frédégonde and Déjanire? After publishing a selection of his correspondence and a book on his travels in the Orient, the Palazzetto Bru Zane has already recorded his cantatas for the Prix de Rome and his operas Les Barbares, Proserpine and Le Timbre d’Argent. Several discs of mélodies – including one with orchestra – have also revealed a subtle and constantly renewed musical style. It therefore seemed only natural for the Centre de musique romantique française to continue its work on this artist by devoting a cycle to him to mark the centenary of his death.

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay