Centred on the composer Louise Farrenc (1804-1875), this cycle celebrates a generation of artists, born at the time of the Napoleonic Empire, who heralded the arrival of musical Romanticism in France.

Cycle

Louise Farrenc, a child of the century

“For Madame Farrenc, it was not enough

to have written so many variations,

rondos and études – works of rare purity –

no, she wanted to get to know all the secrets,

all the processes of orchestration,

and with the same energy she composed works

of the highest order: trios, quartets, quintets,

nonets, overtures and symphonies.”

to have written so many variations,

rondos and études – works of rare purity –

no, she wanted to get to know all the secrets,

all the processes of orchestration,

and with the same energy she composed works

of the highest order: trios, quartets, quintets,

nonets, overtures and symphonies.”

Antoine-François Marmontel, Le Ménestrel, 1877.

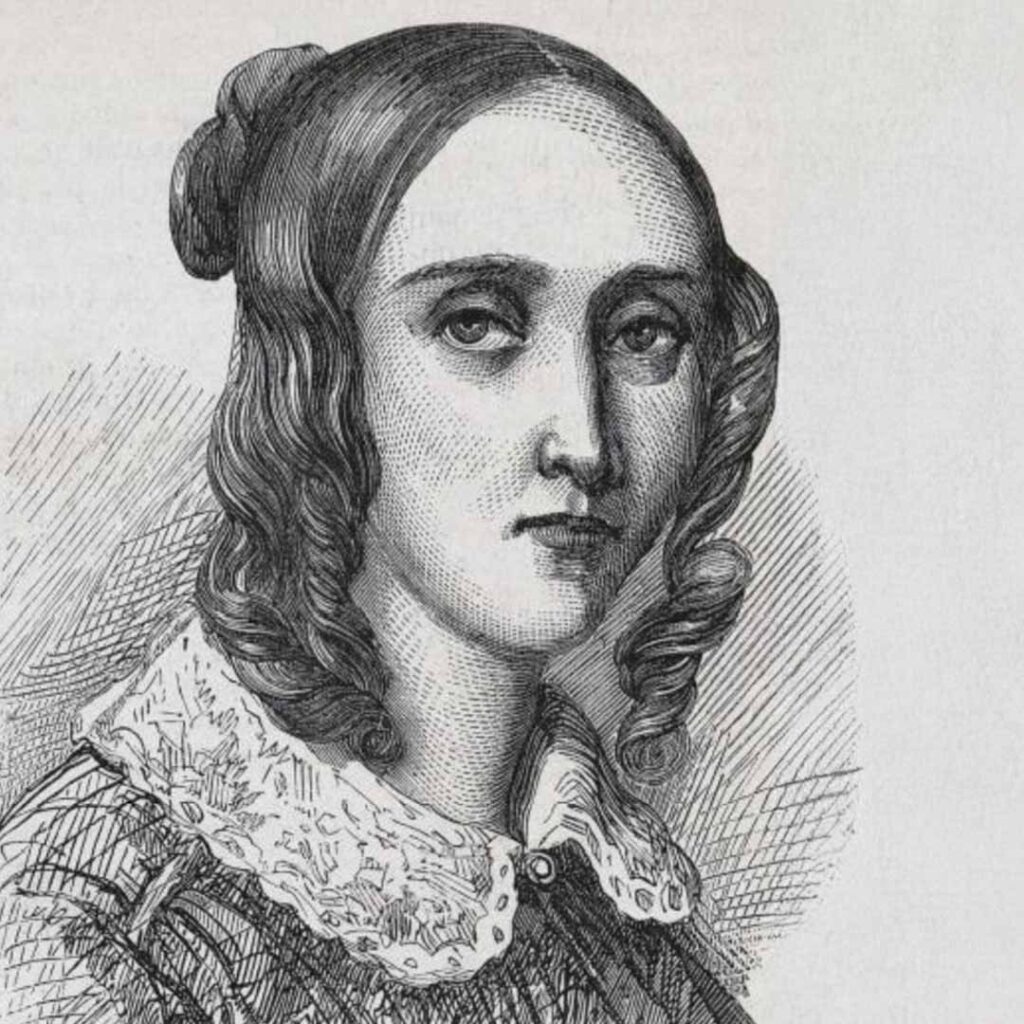

Louise Farrenc

Louise Farrenc, who died 150 years ago, was a remarkable musician. Born into a family that included generations of successful painters, on her mother’s side, and also sculptors (including her father, Jacques-Edme Dumont), she succeeded in making a name for herself in fields – including the composition of symphonic works – that were then considered an exclusively male province. The support and encouragement of her husband, the flautist and music publisher Aristide Farrenc, appears to have been a determining factor in the flourishing of her creative career, but for her renown she was indebted solely to her own talents, first as a virtuoso pianist, then as a composer, with a catalogue including piano works, chamber music – for which, twice, in 1861 and 1869, he won the coveted Prix Chartier awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts – but also orchestral compositions: two overtures and three symphonies, written between 1834 and 1847. The influence of Beethoven is clearly evident in her works. She also played a part in the early music revival in Paris.

Les enfants du siècle

“During the wars of the Empire, whilst husbands and brothers were in Germany, anxious mothers had given birth to an ardent, pale, and neurotic generation.” Alfred de Musset, at the beginning of the second chapter of La Confession d’un enfant du siècle (“The Confession of a Child of the Century”), looked at the children born at the beginning of the nineteenth century, who reached maturity around 1830. They included, in the artistic sphere, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas (born in 1802), Hector Berlioz and Adolphe Adam (1803), George Sand and Louise Farrenc (1804), Louise Bertin (1805), Henri Reber (1807), Gérard de Nerval and Maria Malibran (1808), and Alfred de Musset, Félicien David and Frédéric Chopin (1810). Brought up in veneration of Napoleon (“One man only was then the life of Europe; all other beings struggled to fill their lungs with the air that he had breathed,” wrote Musset), those individuals experienced the fall of the Empire, and grew up to the rhythm of changes of regime and revolutions. The profound change in values that resulted gave rise to a peculiar kind of melancholy: it served as the seedbed for the Romantic movement.

Paris, artistic capital of Europe

In the late 1820s, an ambitious artistic policy brought about a meteoric rise in musical activity in Paris. There was an exponential increase in the number of concerts organised each year, and instrument making – particularly piano making – flourished, as did music publishing. That was also the time of the first specialised music periodicals. The appeal of the French capital is explained, partly at least, by the fact that it had attracted the most prominent composer of the time, Gioachino Rossini, whose works captured the hearts of Parisians during the 1820s, and whose opera Guillaume Tell, a pivotal work in the French repertoire, was first performed there in 1829. In his wake, Hérold, Auber, Halévy and Meyerbeer created the first grands-opéras, revitalised the opéra-comique genre, and completed the task of making their city the artistic capital of Europe. Paris was also noted for the quality of its teaching: the Paris Conservatoire was the largest music school in Europe, drawing from all over the continent virtuosos wishing to perfect their art. And Louise Farrenc was professor of piano at that prestigious institution from 1842 to 1872.

Pianistic virtuosity

Following the example of Paganini for the violin, Romantic composers set about exploring the virtuosic possibilities of the piano. Piano technique, bolstered by advancements in piano manufacturing and the Europe-wide circulation of music scores, moved, especially between 1810 and 1840, towards greater power and velocity. Teaching methods supported that transformation, while countless pieces, by Liszt, Chopin, Alkan, Thalberg and others, put the instrument’s newly acquired capabilities to the test. As pianists succeeded in overcoming difficulties previously considered insurmountable, pianistic virtuosity proved to be the driving force behind a new creativity. Some virtuosos did, however, take things a bit too far, and that was not to everyone’s liking. In 1843 the poet Heinrich Heine criticised excessive virtuosic tours-de-force which “distinctly declare the victory of machinery over mind” and in which he saw only “the transformation of humanity into a tuned instrument of sound [die tonende Instrumentwerdung des Menschen]”. In reaction to the ostentatious frivolity for which some such pieces were criticised, a school of “art sérieux” came into being, taking as its inspiration the works of the great Viennese masters.

Beethoven as the ideal, and the revival of a musical heritage

Louise Farrenc studied composition with Anton Reicha, which meant that she was exposed from an early age to the music of Beethoven. And Beethoven became a life-long reference for her: not only an inspiration for her instrumental music, but also the composer whose works she favoured as a concert pianist. Her veneration for the German composer, shared by Hector Berlioz amongst others, was perfectly in keeping with the times. Indeed, from its foundation in 1828 onwards, the Orchestra of the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire gave prominence to Beethoven’s major symphonic works in its seasons. The concert hall became a sort of museum for displaying to the public the great masters and showcasing the masterpieces of the past. Louise Farrenc’s work in publishing alongside her husband Aristide followed a similar course. Beginning with the complete works of Beethoven, they went on to present a twenty-volume collection of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century keyboard music, Le trésor des pianistes, published from June 1861 to 1872, and including pieces by C.P.E. Bach, François Couperin, Purcell, Handel, Scarlatti, Rameau, Mozart, Clementi and Hummel, amongst others. Louise Farrenc was thus responsible for increasing awareness and appreciation of hitherto largely unknown keyboard pieces from the past.

Louise Farrenc, who died 150 years ago, was a remarkable musician. Born into a family that included generations of successful painters, on her mother’s side, and also sculptors (including her father, Jacques-Edme Dumont), she succeeded in making a name for herself in fields – including the composition of symphonic works – that were then considered an exclusively male province. The support and encouragement of her husband, the flautist and music publisher Aristide Farrenc, appears to have been a determining factor in the flourishing of her creative career, but for her renown she was indebted solely to her own talents, first as a virtuoso pianist, then as a composer, with a catalogue including piano works, chamber music – for which, twice, in 1861 and 1869, he won the coveted Prix Chartier awarded by the Académie des Beaux-Arts – but also orchestral compositions: two overtures and three symphonies, written between 1834 and 1847. The influence of Beethoven is clearly evident in her works. She also played a part in the early music revival in Paris.

Les enfants du siècle

“During the wars of the Empire, whilst husbands and brothers were in Germany, anxious mothers had given birth to an ardent, pale, and neurotic generation.” Alfred de Musset, at the beginning of the second chapter of La Confession d’un enfant du siècle (“The Confession of a Child of the Century”), looked at the children born at the beginning of the nineteenth century, who reached maturity around 1830. They included, in the artistic sphere, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas (born in 1802), Hector Berlioz and Adolphe Adam (1803), George Sand and Louise Farrenc (1804), Louise Bertin (1805), Henri Reber (1807), Gérard de Nerval and Maria Malibran (1808), and Alfred de Musset, Félicien David and Frédéric Chopin (1810). Brought up in veneration of Napoleon (“One man only was then the life of Europe; all other beings struggled to fill their lungs with the air that he had breathed,” wrote Musset), those individuals experienced the fall of the Empire, and grew up to the rhythm of changes of regime and revolutions. The profound change in values that resulted gave rise to a peculiar kind of melancholy: it served as the seedbed for the Romantic movement.

Paris, artistic capital of Europe

In the late 1820s, an ambitious artistic policy brought about a meteoric rise in musical activity in Paris. There was an exponential increase in the number of concerts organised each year, and instrument making – particularly piano making – flourished, as did music publishing. That was also the time of the first specialised music periodicals. The appeal of the French capital is explained, partly at least, by the fact that it had attracted the most prominent composer of the time, Gioachino Rossini, whose works captured the hearts of Parisians during the 1820s, and whose opera Guillaume Tell, a pivotal work in the French repertoire, was first performed there in 1829. In his wake, Hérold, Auber, Halévy and Meyerbeer created the first grands-opéras, revitalised the opéra-comique genre, and completed the task of making their city the artistic capital of Europe. Paris was also noted for the quality of its teaching: the Paris Conservatoire was the largest music school in Europe, drawing from all over the continent virtuosos wishing to perfect their art. And Louise Farrenc was professor of piano at that prestigious institution from 1842 to 1872.

Pianistic virtuosity

Following the example of Paganini for the violin, Romantic composers set about exploring the virtuosic possibilities of the piano. Piano technique, bolstered by advancements in piano manufacturing and the Europe-wide circulation of music scores, moved, especially between 1810 and 1840, towards greater power and velocity. Teaching methods supported that transformation, while countless pieces, by Liszt, Chopin, Alkan, Thalberg and others, put the instrument’s newly acquired capabilities to the test. As pianists succeeded in overcoming difficulties previously considered insurmountable, pianistic virtuosity proved to be the driving force behind a new creativity. Some virtuosos did, however, take things a bit too far, and that was not to everyone’s liking. In 1843 the poet Heinrich Heine criticised excessive virtuosic tours-de-force which “distinctly declare the victory of machinery over mind” and in which he saw only “the transformation of humanity into a tuned instrument of sound [die tonende Instrumentwerdung des Menschen]”. In reaction to the ostentatious frivolity for which some such pieces were criticised, a school of “art sérieux” came into being, taking as its inspiration the works of the great Viennese masters.

Beethoven as the ideal, and the revival of a musical heritage

Louise Farrenc studied composition with Anton Reicha, which meant that she was exposed from an early age to the music of Beethoven. And Beethoven became a life-long reference for her: not only an inspiration for her instrumental music, but also the composer whose works she favoured as a concert pianist. Her veneration for the German composer, shared by Hector Berlioz amongst others, was perfectly in keeping with the times. Indeed, from its foundation in 1828 onwards, the Orchestra of the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire gave prominence to Beethoven’s major symphonic works in its seasons. The concert hall became a sort of museum for displaying to the public the great masters and showcasing the masterpieces of the past. Louise Farrenc’s work in publishing alongside her husband Aristide followed a similar course. Beginning with the complete works of Beethoven, they went on to present a twenty-volume collection of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century keyboard music, Le trésor des pianistes, published from June 1861 to 1872, and including pieces by C.P.E. Bach, François Couperin, Purcell, Handel, Scarlatti, Rameau, Mozart, Clementi and Hummel, amongst others. Louise Farrenc was thus responsible for increasing awareness and appreciation of hitherto largely unknown keyboard pieces from the past.

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay