Sun 14 November

Symposium

Online

Wed 27 April - 20.00

Concert

Choral Music

Sacred Music

Bruxelles

Wed 9 March - 19.30

Opera

Budapest

Wed 22 June - 19.30

Opera

Paris

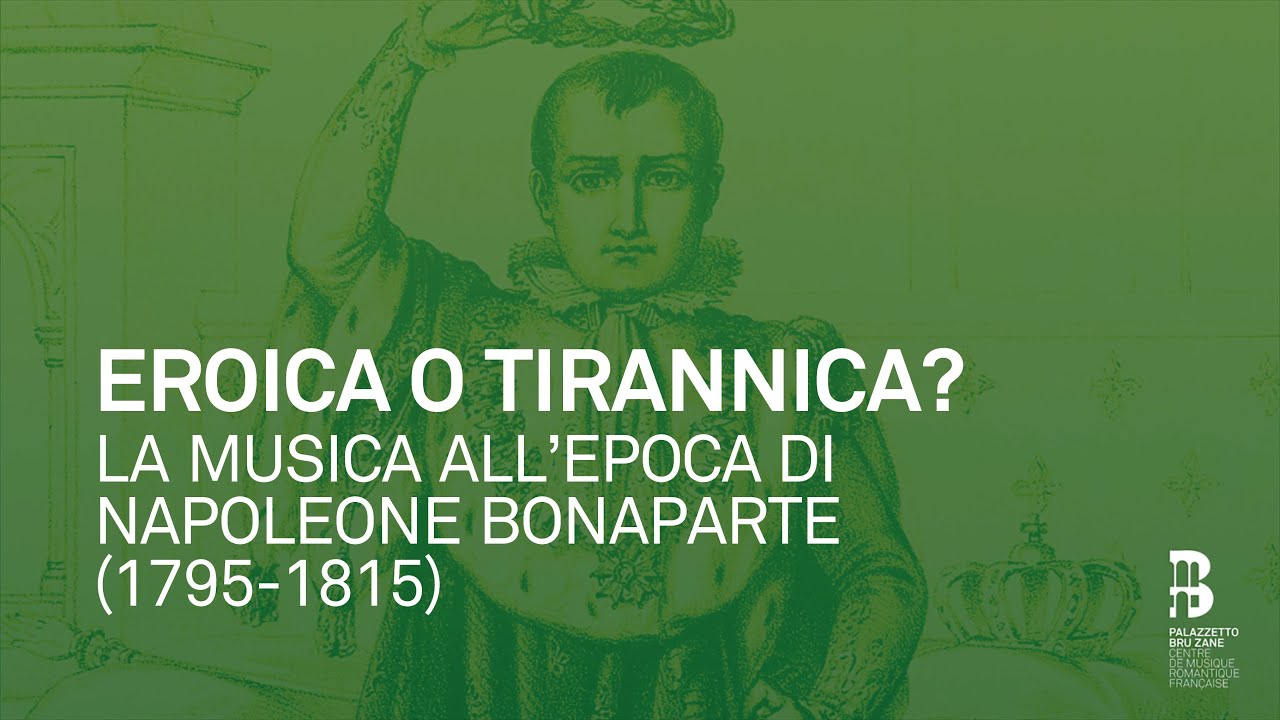

Music at the time of Napoleon Bonaparte (1795-1815)

With the end of the Revolution, hopes and dreams of grandeur accompanied the new century: would Paris become the new musical capital of Europe?

From the end of the Terror until the fall of the Empire, Parisian musical life went through two crucial decades, in terms of both organisation and aesthetic orientation. Yet this pivotal period in the history of European music remains little known, overshadowed as it is by the towering career of Beethoven. It is nevertheless indispensable to examine it in order to grasp both the source of the French Romantic ideal and the manner in which the legacy of the Revolution was absorbed. Divided into three political phases – the Directory (1795-99), the Consulate (1799-1804) and the Empire (1804-15) – the period gradually reverted to an authoritarian regime, which had serious consequences for the contemporary output of music, increasingly under surveillance, but brought opportunities with the foundation of the Conservatoire and the subsequent return to prominence of the city’s opera houses and the restoration of an imperial music establishment consisting of the Chapelle (church music) and the Musique particulière (secular chamber music). Moreover, as the defence of an endangered homeland was gradually transformed into an urge for universal conquest, the artistic community was entrusted with a double mission: to assimilate the spoils of war taken from the occupied territories and to spread its influence throughout Europe.

The ‘Grande École’

Under the Ancien Régime, the French musical world depended almost entirely on the support of the nobility and the clergy. By destabilising these two groups, the Revolution disrupted earlier artistic practices throughout the country. Nevertheless, it offered another path: a form of ‘state music’, charged with educating the citizens in new ideas and love of the Republic, within the context of public festivals or in the opera house. The Conservatoire, founded in Paris in 1795, was the symbol of this evolution, concentrating the key forces of French music in one place. Composers and virtuosos gathered there to train a new generation of artists, capable of competing with and even surpassing students educated under foreign tyrannies. These unprecedented financial efforts quickly bore fruit and enabled Parisian orchestras to establish a new standard of excellence. However, owing to a lack of resources and despite the existence of a number of projects presented during the following decade, it proved unfeasible to create a school of this type outside Paris, thus ushering in a policy of extreme centralisation. The influence of the Conservatoire – at that time the largest music school in Europe – was instead assured by the dissemination of ‘official’ methods: between 1801 and 1814, fourteen pedagogical works were published to propagate a modern style of teaching, founded on a rational, progressive approach to theoretical, vocal and instrumental subjects.

The glory of the Emperor

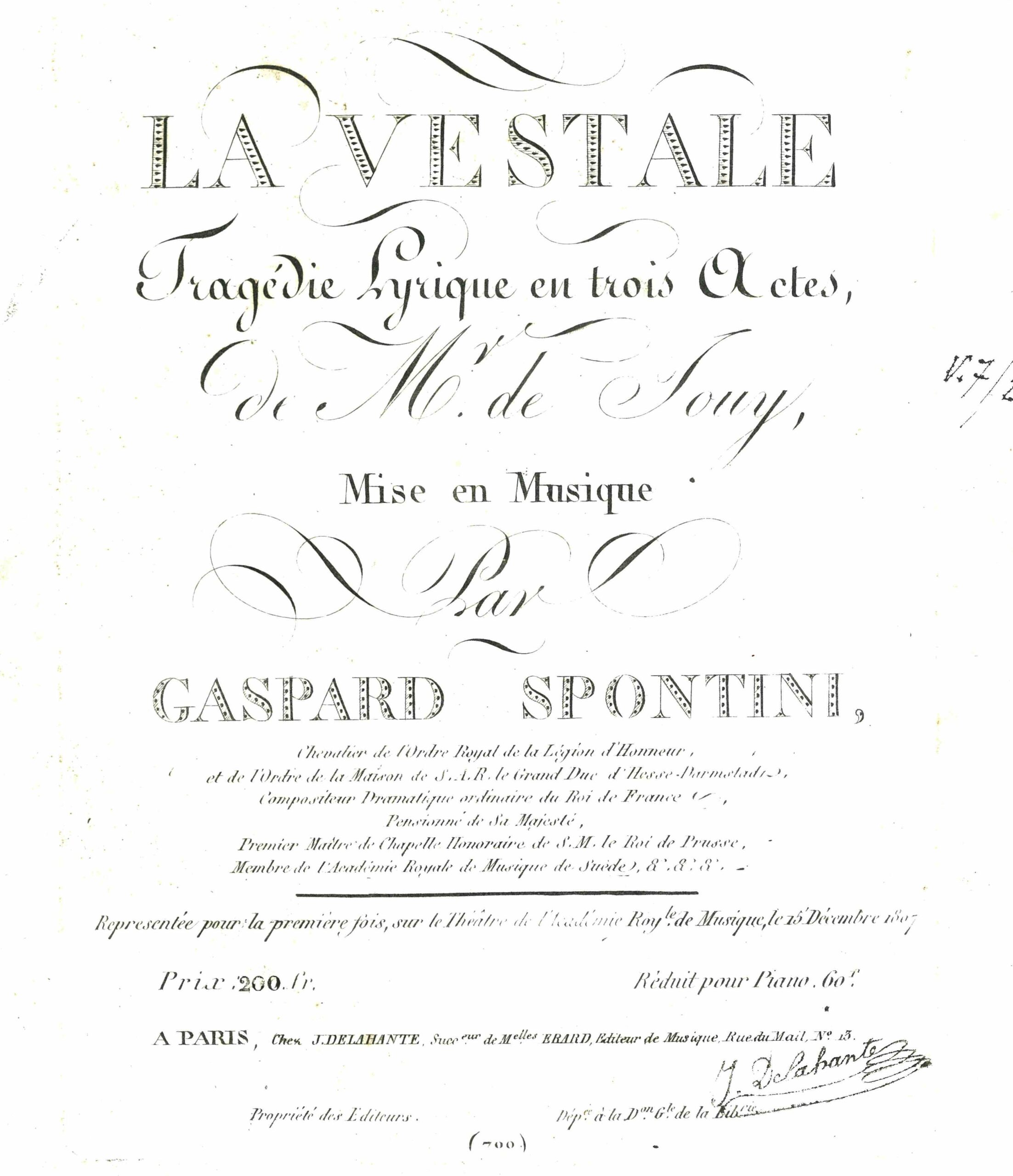

By establishing a state music system, the Republic prepared the ground for imperial propaganda, which was especially perceptible on the operatic stage. The figure of the military leader – most often a Roman general or a Greek hero – was omnipresent in both opera and ballet. Aware of the benefits he could derive from the prestige of the Paris Opéra, Bonaparte worked, from the Consulate onwards, to restore the splendour of the capital’s leading opera house, ordering its administrative reorganisation and controlling its repertory. He then gave it a monopoly on music sung entirely in French and granted it substantial resources. The objective was for the Académie Impériale de Musique – like the Conservatoire – to shine like a beacon throughout Europe, as much for the beauty of its repertory as for the excellence of its performers and the splendour of its staging. This policy gave priority to French composers – Kreutzer, Catel, Le Sueur and Berton in particular – but also relied on foreign creators. Works by Mozart, whom France finally applauded in the pasticcio Les Mystères d’Isis, Paisiello and above all Spontini achieved great success at the Opéra and helped to change the aesthetic contours of a native musical output still heavily influenced by the Gluckian reform. The fall of the Empire led to the disappearance of this repertory, but later revivals of it made a profound impact on the Romantics, as may be seen from Hector Berlioz’s admiring comments on La Mort d’Abel in 1823 and La Vestale in 1852.

Reactionary or pioneer?

The salons of the Empire

Following their exile in Russia, England or the German-speaking countries, the aristocrats who had survived the Revolution returned to France with a new fondness for private musical gatherings. The revival of musical salons in France, which began during the Directory period, reached its height under the Empire and generated a wide variety of musical material, from accompanied vocal romances to highly elaborate chamber music. The spaces in which it could be performed were equally numerous and diversified. Ingres hosted quartet evenings every Friday in the Jardin des Capucines, and Sophie Gail received singers currently fashionable in the capital. The most brilliant of these salons was undoubtedly that of the Prince de Chimay, located in the rue de Babylone, which assembled an orchestra of the leading Paris virtuosos, including the violinists Kreutzer, Rode and Baillot, sometimes playing their own works. The Emperor himself organised private concerts at the Tuileries, notably to mark his birthday, 15 August. While vocal music was generally the repertory of choice on these occasions, the Empress Joséphine organised weekly chamber music concerts at the Château de Malmaison, which attracted the finest artists from Paris to play with the harp of the Nadermann brothers and the horn of Frédéric Duvernoy. Meanwhile, in the homes of the upper bourgeoisie, many amateurs, men and women, began playing the pianoforte.

Italy in Paris

Although the Opéra obtained the Emperor’s support for political reasons, the development of an Italian opera house in Paris was due to Napoleon Bonaparte’s personal taste for transalpine music, which probably dated from his Corsican childhood and was reinvigorated after the Italian campaign. The presence of bel canto in the capital was nothing new at the beginning of the nineteenth century: as early as 1752, a troupe of Italian singers occasionally occupied the stage of the Académie Royale de Musique. However, this type of activity did not achieve permanent status until 1801, with a company initially named ‘Opera-Buffa’ and later (in 1804) ‘Théâtre de l’Impératrice’. Accustomed to discovering foreign works in translation, the Parisian public was now able to enjoy the masterpieces of Cimarosa, Paisiello, Paer and Mozart in the original language. The French occupation of large swathes of Italian territory made it easier for works and artists to gravitate to this Théâtre-Italien, giving it the air of an authentic Neapolitan house. In the light of its success, the press wondered what one should think of these performances, to which the public flocked without immediately grasping the meaning of the words, and heedless of the often poor quality of the librettos. Was it reasonable to enjoy an opera solely for its music? In the midst of these heated debates, contemporaries realised they were moving into a new aesthetic era, in which the abandonment of the primacy given to the text opened the way to the musical expression of feelings.

Programme

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay