Crazy, mad, ludicrous, brimming with fun and full of variety: the festive and satirical spirit of the second half of the nineteenth century is with us this season at the occasion of the bicentenary of the birth of Hervé (1825-1892).

Cycle

Folies parisiennes

“Pray show a little courage,

Monsieur Perrin; I swear to you

that I am no more a fool than Wagner or Verdi.

Forget the Foreigner for a while

and allow your devoted Parisian

to set a libretto.”

Monsieur Perrin; I swear to you

that I am no more a fool than Wagner or Verdi.

Forget the Foreigner for a while

and allow your devoted Parisian

to set a libretto.”

Letter from Hervé to Émile Perrin, director of the Paris Opéra, 1868.

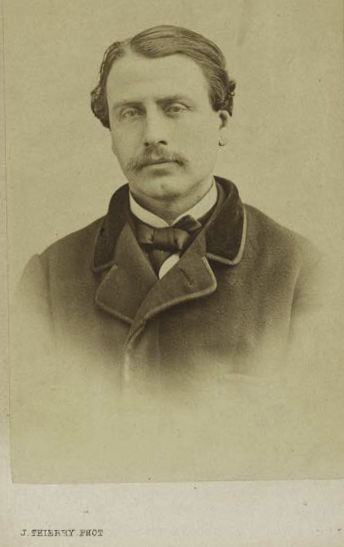

Hervé bicentenary (1825-1892)

With its decision to extend its scientific research and artistic proposals to the “lighter” genres, the composer Hervé has been one of the Palazzetto Bru Zane’s main focuses in recent seasons. Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde, Mam’zelle Nitouche, Le Compositeur toqué, Le Retour d’Ulysse, V’lan dans l’œil, Moldave et Circassienne: all these works have returned to the stage to raise awareness of the unique humour of an author who has all too often been left in the shadow of his contemporary and rival, Jacques Offenbach. To celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of this prolific composer of zany comedies, the “Folies parisiennes” cycle sets him at the heart of an artistic movement which, from the Second Empire to the Belle Époque, relied on the absurd and the ridiculous to provide entertainment with a wide appeal.

The birth of opérette

Buoyed by the phenomenal success of the great Romantic opera, the operatic world in mid-nineteenth-century France tended to take things, even opéra-comique, very seriously. In reaction, but also in response to popular demand, two composers set about creating new venues where levity and laughter would have their rightful place – a task that proved far from easy, however. The system of privileges then in place gave a monopoly to the four national flagship theatres: the Paris Opéra (known at that time as the Académie Imperiale de Musique), the Opéra-Comique, the Théâtre-Italien and the Théâtre-Lyrique. Opening the Folies-Concertantes (Hervé, 1854) and the Bouffes-Parisiens (Offenbach, 1855) called for a great deal of ingenuity and a certain degree of complicity with the powers that be. Furthermore, ways had to be found to circumvent the bans. No more than two singers allowed on stage? Then for a trio, we’ll have the third singer in the wings. The staging of dramatic works is forbidden? Well, then let’s present crazy pieces that make no sense at all. With the increasing success of the Bouffes-Parisiens, the theatre obtained more and more privileges, and Offenbach’s two-act Orphée aux Enfers of 1858 marked the entry of opéra-bouffe into the big leagues.

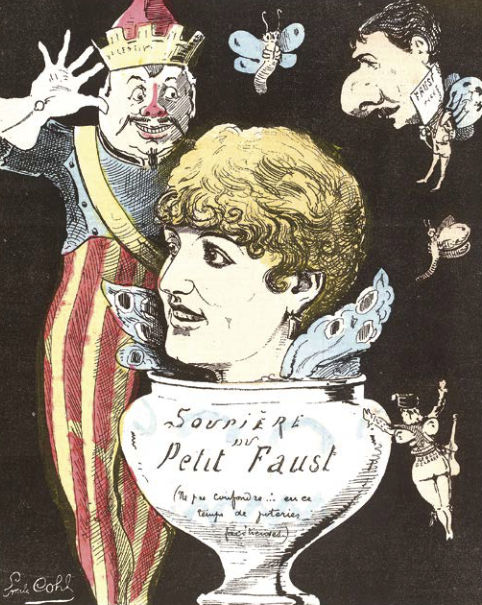

Opéra-bouffe

Hervé was not involved in the creation of the opéra-bouffe genre. At the time of Offenbach’s early triumphs, he was in prison for corruption of a minor, then in exile in Montpellier, Marseille and Cairo. On his return to Paris in the mid-1860s he showed a singular ability to adapt to a new situation: with the 1864 legislation deregulating Parisian theatres, works presented on stages other than those of the four “flagships” were no longer limited in length or in the number of characters permitted. Hervé’s Le Joueur de flûte, L’Œil crevé, Chilpéric, Le Petit Faust and Les Turcs delighted the same Parisian audiences that applauded Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène, La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein, La Périchole and Les Brigands. And that repertoire was also taken to other cities in France, as well as abroad: Hervé in London and Offenbach in the United States both met with success. But just when the satirical spirit of the opéra-bouffe genre was beginning to enjoy international acclaim, the French military defeat at the hands of Prussia in 1870 brought its triumph in Paris to an abrupt halt. Contrition was the order of the day and France was soon to find itself under the rule of the conservative and monarchic government of those years known as the Moral Order. The folies of the Second Empire were over.

At the café-concert

The café-concert became an important entertainment venue in the nineteenth century. Evening performances would consist of a series of short numbers, in which music featured alongside acrobatics, dancing, mime, magic, poetry, animal acts, and so on. Variety was the key to holding the audience’s attention. A number expressing pathos might be followed by one causing hilarity, titillating the audience or presenting a parody. The musical style was light and simple: catchy melodies, easy to memorise, that could be sung at home with the aid of a piano or a guitar. Star performers played a part in popularising comic songs or scenes. The singer Thérésa and the chanteur agité Paulus were among the first, soon to be joined by Yvette Guilbert and Aristide Bruant. The latter, one of bohemian Montmartre’s most influential figures, died in 1925, so this season we shall be commemorating the centenary of his death.

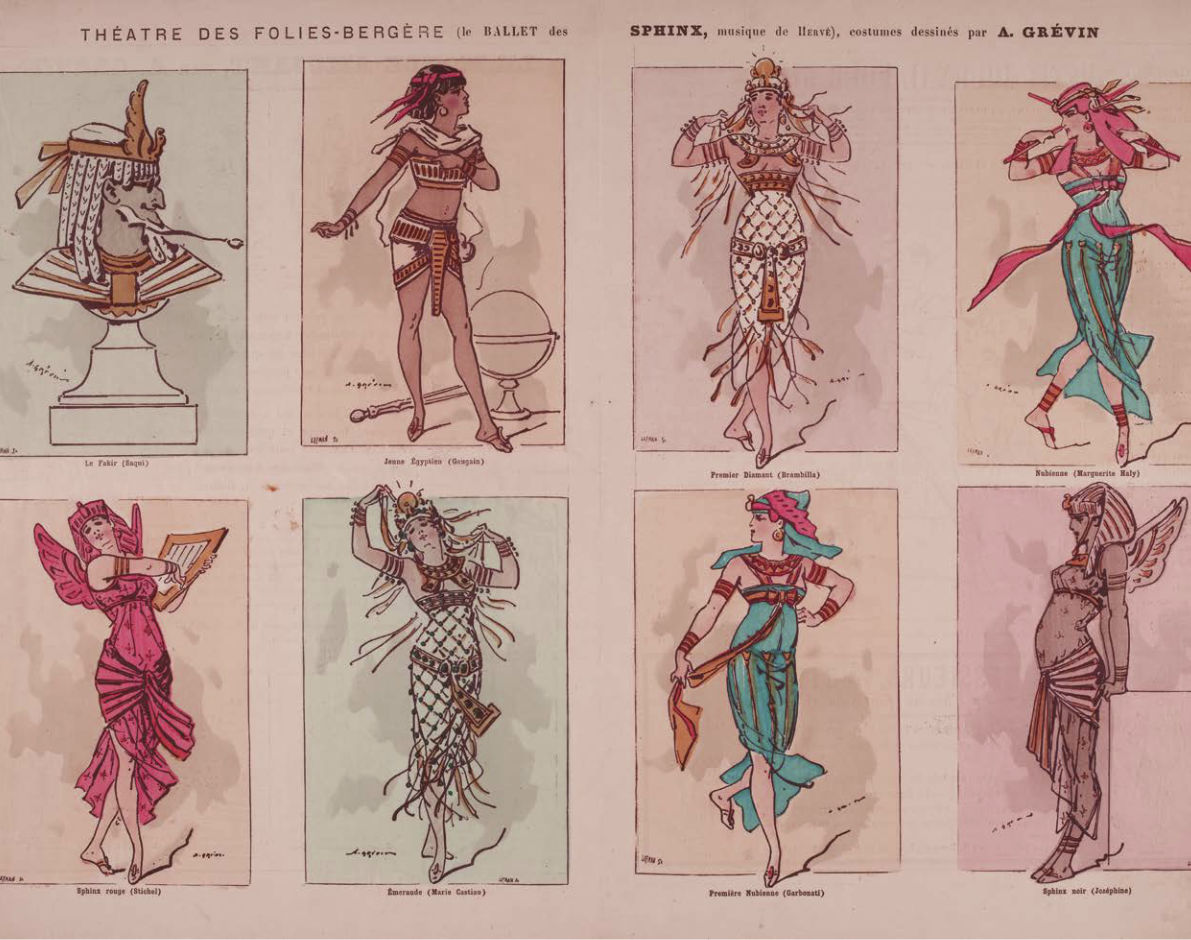

La folie des grandeurs

Popular genres were not to be outdone. With grand-opéra Parisian audiences had become accustomed to splendid displays on stage, with multiple lavish sets, rich and elaborate costumes, impressive pyrotechnics…, and the less serious genres had no hesitation in following suit. During the Third Republic, venues such as the Théâtre du Châtelet and the Théâtre de la Gaîté, turning to the fairy-tale aesthetic known as féerie, presented spectacular works with a multiplicity of “tableaux”. One such opéra-féerie was Le Voyage dans la Lune (1875) by Offenbach, requiring twenty-three scene changes and transporting audiences not only to the moon, but also from a glass palace via mother-of-pearl galleries to a volcano. While Offenbach took inspiration for the latter from a novel by Jules Verne, his rival Hervé turned to Middle Eastern folktales (Aladdin the Second, premièred in London in 1870, and Les Mille et une Nuits for the Châtelet in 1882), and he was soon joined by Charles Lecocq (Ali-Baba, 1887). Others revisited some of the folktales that had been retold by Charles Perrault: Jules Massenet chose Cendrillon (1899), Charles Silver took up La Belle au bois dormant (1902); as for Félix Fourdrain, he composed Les Contes de Perrault (1913). All of these are what are known as opéras-féeries.

With its decision to extend its scientific research and artistic proposals to the “lighter” genres, the composer Hervé has been one of the Palazzetto Bru Zane’s main focuses in recent seasons. Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde, Mam’zelle Nitouche, Le Compositeur toqué, Le Retour d’Ulysse, V’lan dans l’œil, Moldave et Circassienne: all these works have returned to the stage to raise awareness of the unique humour of an author who has all too often been left in the shadow of his contemporary and rival, Jacques Offenbach. To celebrate the bicentenary of the birth of this prolific composer of zany comedies, the “Folies parisiennes” cycle sets him at the heart of an artistic movement which, from the Second Empire to the Belle Époque, relied on the absurd and the ridiculous to provide entertainment with a wide appeal.

The birth of opérette

Buoyed by the phenomenal success of the great Romantic opera, the operatic world in mid-nineteenth-century France tended to take things, even opéra-comique, very seriously. In reaction, but also in response to popular demand, two composers set about creating new venues where levity and laughter would have their rightful place – a task that proved far from easy, however. The system of privileges then in place gave a monopoly to the four national flagship theatres: the Paris Opéra (known at that time as the Académie Imperiale de Musique), the Opéra-Comique, the Théâtre-Italien and the Théâtre-Lyrique. Opening the Folies-Concertantes (Hervé, 1854) and the Bouffes-Parisiens (Offenbach, 1855) called for a great deal of ingenuity and a certain degree of complicity with the powers that be. Furthermore, ways had to be found to circumvent the bans. No more than two singers allowed on stage? Then for a trio, we’ll have the third singer in the wings. The staging of dramatic works is forbidden? Well, then let’s present crazy pieces that make no sense at all. With the increasing success of the Bouffes-Parisiens, the theatre obtained more and more privileges, and Offenbach’s two-act Orphée aux Enfers of 1858 marked the entry of opéra-bouffe into the big leagues.

Opéra-bouffe

Hervé was not involved in the creation of the opéra-bouffe genre. At the time of Offenbach’s early triumphs, he was in prison for corruption of a minor, then in exile in Montpellier, Marseille and Cairo. On his return to Paris in the mid-1860s he showed a singular ability to adapt to a new situation: with the 1864 legislation deregulating Parisian theatres, works presented on stages other than those of the four “flagships” were no longer limited in length or in the number of characters permitted. Hervé’s Le Joueur de flûte, L’Œil crevé, Chilpéric, Le Petit Faust and Les Turcs delighted the same Parisian audiences that applauded Offenbach’s La Belle Hélène, La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein, La Périchole and Les Brigands. And that repertoire was also taken to other cities in France, as well as abroad: Hervé in London and Offenbach in the United States both met with success. But just when the satirical spirit of the opéra-bouffe genre was beginning to enjoy international acclaim, the French military defeat at the hands of Prussia in 1870 brought its triumph in Paris to an abrupt halt. Contrition was the order of the day and France was soon to find itself under the rule of the conservative and monarchic government of those years known as the Moral Order. The folies of the Second Empire were over.

At the café-concert

The café-concert became an important entertainment venue in the nineteenth century. Evening performances would consist of a series of short numbers, in which music featured alongside acrobatics, dancing, mime, magic, poetry, animal acts, and so on. Variety was the key to holding the audience’s attention. A number expressing pathos might be followed by one causing hilarity, titillating the audience or presenting a parody. The musical style was light and simple: catchy melodies, easy to memorise, that could be sung at home with the aid of a piano or a guitar. Star performers played a part in popularising comic songs or scenes. The singer Thérésa and the chanteur agité Paulus were among the first, soon to be joined by Yvette Guilbert and Aristide Bruant. The latter, one of bohemian Montmartre’s most influential figures, died in 1925, so this season we shall be commemorating the centenary of his death.

La folie des grandeurs

Popular genres were not to be outdone. With grand-opéra Parisian audiences had become accustomed to splendid displays on stage, with multiple lavish sets, rich and elaborate costumes, impressive pyrotechnics…, and the less serious genres had no hesitation in following suit. During the Third Republic, venues such as the Théâtre du Châtelet and the Théâtre de la Gaîté, turning to the fairy-tale aesthetic known as féerie, presented spectacular works with a multiplicity of “tableaux”. One such opéra-féerie was Le Voyage dans la Lune (1875) by Offenbach, requiring twenty-three scene changes and transporting audiences not only to the moon, but also from a glass palace via mother-of-pearl galleries to a volcano. While Offenbach took inspiration for the latter from a novel by Jules Verne, his rival Hervé turned to Middle Eastern folktales (Aladdin the Second, premièred in London in 1870, and Les Mille et une Nuits for the Châtelet in 1882), and he was soon joined by Charles Lecocq (Ali-Baba, 1887). Others revisited some of the folktales that had been retold by Charles Perrault: Jules Massenet chose Cendrillon (1899), Charles Silver took up La Belle au bois dormant (1902); as for Félix Fourdrain, he composed Les Contes de Perrault (1913). All of these are what are known as opéras-féeries.

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay