To mark the centenary of his death in 1924, the Palazzetto Bru Zane honours Gabriel Fauré in the company of the artists he trained.

Cycle

Fauré and his pupils

‘For me, art,

and music especially,

consists in raising ourselves

as far as possible above what is.’

Gabriel Fauré to his son, 1908

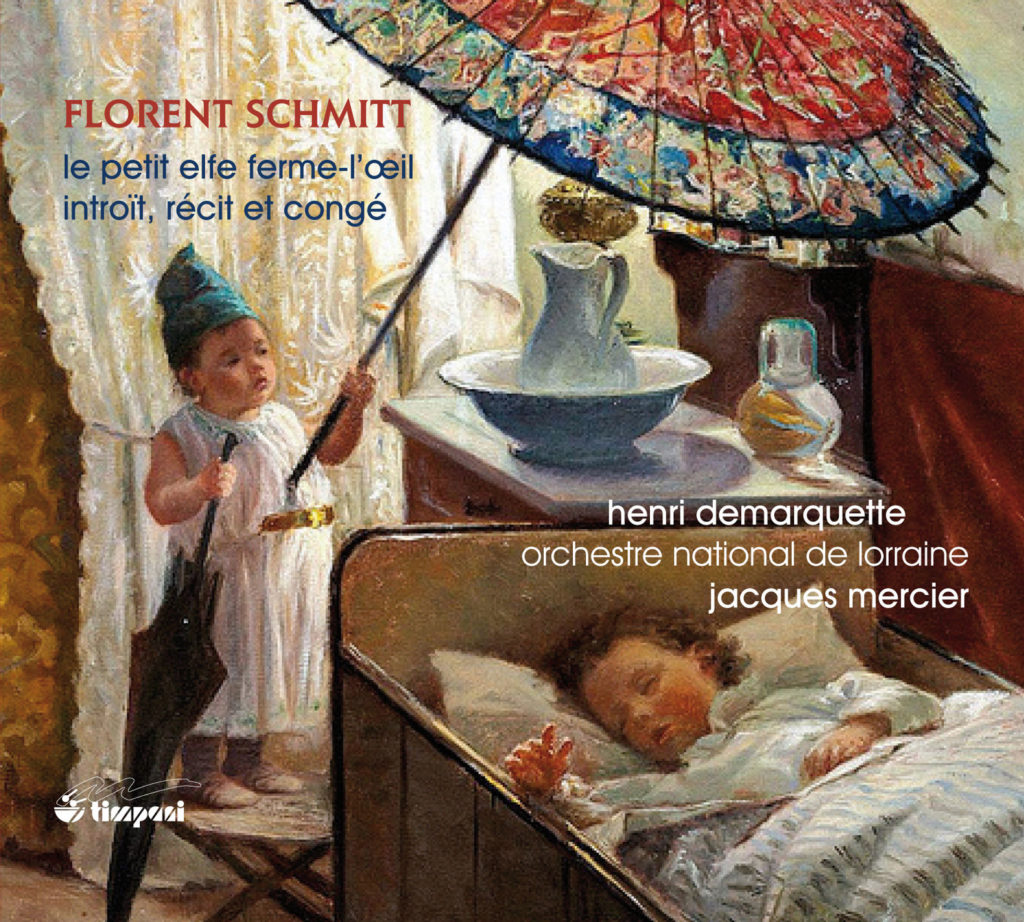

The task of turning the page on Romanticism and calming the deep divisions in the French musical world at the dawn of the twentieth century fell to a figure with an atypical career trajectory and indisputable artistic merits. Gabriel Fauré had not studied at the Paris Conservatoire, and his first masterpieces had not been written for the operatic stage. A student of Saint-Saëns at the École Niedermeyer, he initially found outlets for his music at avant-garde concerts, in churches and in the salons. In a France torn apart by the Dreyfus affair, he embodied a compromise as much as a new path. His influence as a teacher of composition deserves to be explored anew: it was felt by a number of musicians who were to enjoy remarkable careers, including Nadia Boulanger, George Enescu, Charles Koechlin, Maurice Ravel and Florent Schmitt.

An atypical career

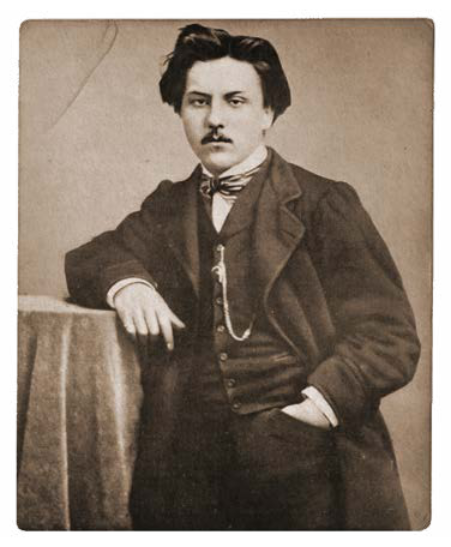

For a nineteenth-century French composer, the road to glory usually followed several immutable staging-points: a brilliant course of studies at the Paris Conservatoire, the award of the Prix de Rome for musical composition, and the production of operatic works. No one could hope to attain the most prestigious positions or receive the highest honours if they did not follow this typical career path. Gabriel Fauré was the first to manage it by following an entirely different itinerary. The son of the headmaster of a teacher training college, Fauré was sent at the age of nine to the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse, recently founded by Louis Niedermeyer. As a pupil of Clément Loret (organ), Camille Saint-Saëns (piano) and Louis Niedermeyer himself (composition), he received an exceptionally wide-ranging artistic education – oriented as much towards the old masters as the moderns – but one that destined him for no other career than that of a church musician. He duly embarked on this as soon as he finished his studies (1865) and achieved distinction at La Madeleine as maître de chapelle (1877-1905), then organist (1896-1905). His Requiem (1888), now a key work in the French repertory, epitomises on its own his mastery of sacred composition.

In the salons of high society

Alongside his career as organist and choirmaster, Gabriel Fauré showed another side of his talent in the leading Parisian salons. Taken up by influential patrons, in particular the Princesse de Polignac, he received from the French aristocracy an extraordinary degree of financial support, but also access to a powerful forum for expression perfectly suited to his sensibilities. From his op.1 (Le Papillon et la Fleur, based on a text by Victor Hugo, in 1857) to his twilight years (the cycle L’Horizon chimérique premiered in May 1922), Fauré indefatigably explored the genre of French mélodie: his catalogue includes no fewer than 111 songs. During his lifetime, he established himself as the undisputed master of the genre, and in 1911 he set out his conception of how poems should be set to music: the harmony should ‘underline the deep-seated sentiment that the words merely sketch out’. He also threw himself with gusto into the realm of chamber music in his capacity as a member of the Société Nationale de Musique. From the Violin Sonata no.1 (1877) and Piano Quartet no.1 (1880) to the Piano Quintet no.2 (1921) and String Quartet (1924), he left posterity half a century’s worth of subtle instrumental experimentation.

At the Conservatoire

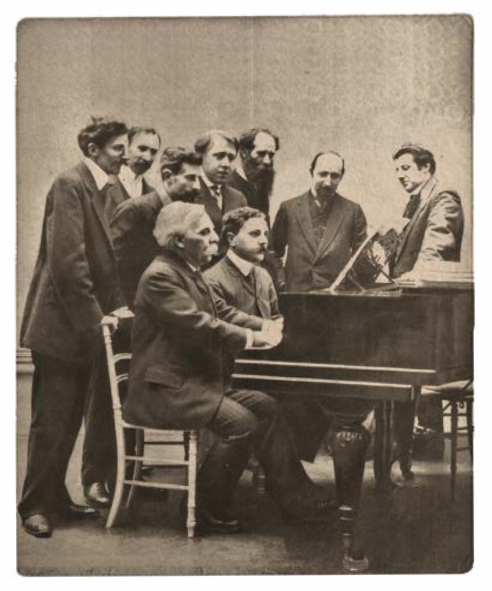

Although Fauré’s mélodies and chamber pieces were in themselves a course of composition upon which the younger generation drew abundantly, his influence on them became more direct towards the end of his life. Long excluded from the most prestigious academic posts, in 1896 he seized the opportunity of Jules Massenet’s resignation to obtain a position as professor of composition at the Conservatoire. His class, which he taught for ten years before being appointed director of the establishment, included some of the great future hopes of French music, such as Florent Schmitt, Charles Koechlin, George Enescu, Nadia Boulanger, Jean Roger-Ducasse and Maurice Ravel. His time in office also marked a turning point: the Prix de Rome competition was finally opened to women after a century of existence, and it is to the protests of one of his students, Juliette Toutain, that we owe this development in 1903. Fauré’s appointment as head of the Conservatoire, too, was due to a very specific context: with the Schola Cantorum challenging the supremacy of the older institution and France divided over the Dreyfus affair and religious issues, the appointment of a former pupil of the École Niedermeyer in 1905 appeared as a gesture of appeasement.

A tutelary figure

The beginning of the twentieth century saw the official consecration of Fauré. After finally bowing to the operatic mores of his time with Prométhée, premiered at the Béziers Arena (1900) – to be followed a decade later by Pénélope at the Théâtre de Monte-Carlo (1913) – he was appointed director of the Conservatoire (1905) and then elected to the Institut (1909). He also established a reputation in the concert hall with the success of the Pavane and the incidental music for Pelléas et Mélisande. While one might imagine this final stage constituted a move into the academic camp, or think that, as he grew older, he would have clung to an outdated aesthetic, Fauré showed himself to be perfectly attuned to the aspirations of his pupils. When the Société Nationale de Musique refused to programme works by his students, a split occurred, giving rise to the Société Musicale Indépendante (1910). Spearheaded by Ravel, Vuillermoz, Schmitt, Caplet, Koechlin, Aubert and Roger-Ducasse, this new body escaped the ire of its detractors by placing itself under the protection of Fauré, who became its president. As a protector and source of inspiration, he had a lasting influence on French modernism.

An atypical career

For a nineteenth-century French composer, the road to glory usually followed several immutable staging-points: a brilliant course of studies at the Paris Conservatoire, the award of the Prix de Rome for musical composition, and the production of operatic works. No one could hope to attain the most prestigious positions or receive the highest honours if they did not follow this typical career path. Gabriel Fauré was the first to manage it by following an entirely different itinerary. The son of the headmaster of a teacher training college, Fauré was sent at the age of nine to the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse, recently founded by Louis Niedermeyer. As a pupil of Clément Loret (organ), Camille Saint-Saëns (piano) and Louis Niedermeyer himself (composition), he received an exceptionally wide-ranging artistic education – oriented as much towards the old masters as the moderns – but one that destined him for no other career than that of a church musician. He duly embarked on this as soon as he finished his studies (1865) and achieved distinction at La Madeleine as maître de chapelle (1877-1905), then organist (1896-1905). His Requiem (1888), now a key work in the French repertory, epitomises on its own his mastery of sacred composition.

In the salons of high society

Alongside his career as organist and choirmaster, Gabriel Fauré showed another side of his talent in the leading Parisian salons. Taken up by influential patrons, in particular the Princesse de Polignac, he received from the French aristocracy an extraordinary degree of financial support, but also access to a powerful forum for expression perfectly suited to his sensibilities. From his op.1 (Le Papillon et la Fleur, based on a text by Victor Hugo, in 1857) to his twilight years (the cycle L’Horizon chimérique premiered in May 1922), Fauré indefatigably explored the genre of French mélodie: his catalogue includes no fewer than 111 songs. During his lifetime, he established himself as the undisputed master of the genre, and in 1911 he set out his conception of how poems should be set to music: the harmony should ‘underline the deep-seated sentiment that the words merely sketch out’. He also threw himself with gusto into the realm of chamber music in his capacity as a member of the Société Nationale de Musique. From the Violin Sonata no.1 (1877) and Piano Quartet no.1 (1880) to the Piano Quintet no.2 (1921) and String Quartet (1924), he left posterity half a century’s worth of subtle instrumental experimentation.

At the Conservatoire

Although Fauré’s mélodies and chamber pieces were in themselves a course of composition upon which the younger generation drew abundantly, his influence on them became more direct towards the end of his life. Long excluded from the most prestigious academic posts, in 1896 he seized the opportunity of Jules Massenet’s resignation to obtain a position as professor of composition at the Conservatoire. His class, which he taught for ten years before being appointed director of the establishment, included some of the great future hopes of French music, such as Florent Schmitt, Charles Koechlin, George Enescu, Nadia Boulanger, Jean Roger-Ducasse and Maurice Ravel. His time in office also marked a turning point: the Prix de Rome competition was finally opened to women after a century of existence, and it is to the protests of one of his students, Juliette Toutain, that we owe this development in 1903. Fauré’s appointment as head of the Conservatoire, too, was due to a very specific context: with the Schola Cantorum challenging the supremacy of the older institution and France divided over the Dreyfus affair and religious issues, the appointment of a former pupil of the École Niedermeyer in 1905 appeared as a gesture of appeasement.

A tutelary figure

The beginning of the twentieth century saw the official consecration of Fauré. After finally bowing to the operatic mores of his time with Prométhée, premiered at the Béziers Arena (1900) – to be followed a decade later by Pénélope at the Théâtre de Monte-Carlo (1913) – he was appointed director of the Conservatoire (1905) and then elected to the Institut (1909). He also established a reputation in the concert hall with the success of the Pavane and the incidental music for Pelléas et Mélisande. While one might imagine this final stage constituted a move into the academic camp, or think that, as he grew older, he would have clung to an outdated aesthetic, Fauré showed himself to be perfectly attuned to the aspirations of his pupils. When the Société Nationale de Musique refused to programme works by his students, a split occurred, giving rise to the Société Musicale Indépendante (1910). Spearheaded by Ravel, Vuillermoz, Schmitt, Caplet, Koechlin, Aubert and Roger-Ducasse, this new body escaped the ire of its detractors by placing itself under the protection of Fauré, who became its president. As a protector and source of inspiration, he had a lasting influence on French modernism.

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay