Georges Bizet, who died 150 years ago, marked his era with an avant-garde musical production.

A look back at a legacy that extends far beyond the success of Carmen.

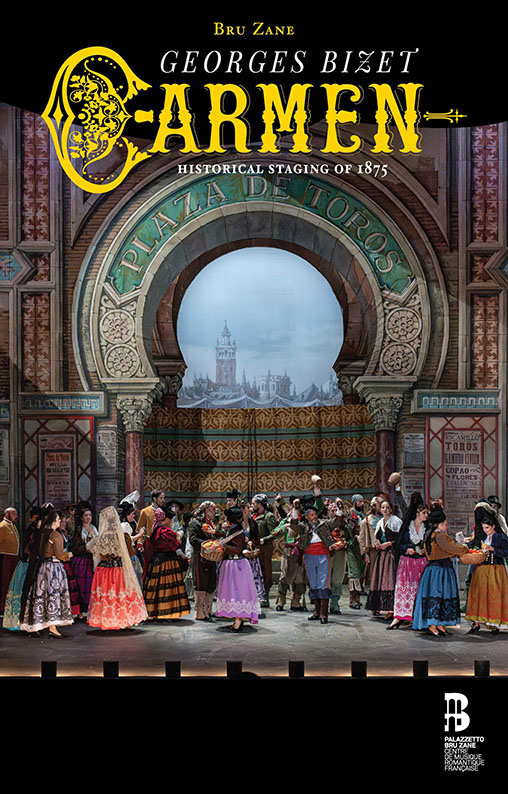

The composer of the most frequently performed French opera in the world today, Georges Bizet (1838-1875), died at the age of 36, so did not live long enough to enjoy its success. Legend has it that the poor reception of Carmen was to blame for his death. Albeit an exaggeration, that does give us some indication of what the avant-garde artist had to contend with at that time: indeed, between the 1850s and the 1870s Bizet composed a body of work that was not fully appreciated until the 1880s onwards. A brilliant student at the Paris Conservatoire, a winner of the Prix de Rome, an active member of the Société nationale de musique, he belonged to the generation that was born just as Romanticism was emerging – a generation that was therefore responsible for strengthening the movement by bringing in new ideas. However, audiences were not yet ready for that.

‘We have come to the point where any composer today who is concerned with scenic effect and the expression of feelings and characters is infallibly accused of Wagnerism.’

(Johannes Weber, Le Temps, 5 June 1872)

A look back at a legacy that extends far beyond the success of Carmen.

The composer of the most frequently performed French opera in the world today, Georges Bizet (1838-1875), died at the age of 36, so did not live long enough to enjoy its success. Legend has it that the poor reception of Carmen was to blame for his death. Albeit an exaggeration, that does give us some indication of what the avant-garde artist had to contend with at that time: indeed, between the 1850s and the 1870s Bizet composed a body of work that was not fully appreciated until the 1880s onwards. A brilliant student at the Paris Conservatoire, a winner of the Prix de Rome, an active member of the Société nationale de musique, he belonged to the generation that was born just as Romanticism was emerging – a generation that was therefore responsible for strengthening the movement by bringing in new ideas. However, audiences were not yet ready for that.

‘We have come to the point where any composer today who is concerned with scenic effect and the expression of feelings and characters is infallibly accused of Wagnerism.’

(Johannes Weber, Le Temps, 5 June 1872)

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay