Fri 27 May - 19.30

Concert

Venice

Wed 1 June - 19.30

Opera

Paris

Thu 2 June - 20.30

Concert

Symphonic Music

Paris

Sun 19 June - 16.30

Concert

Symphonic Music

Paris

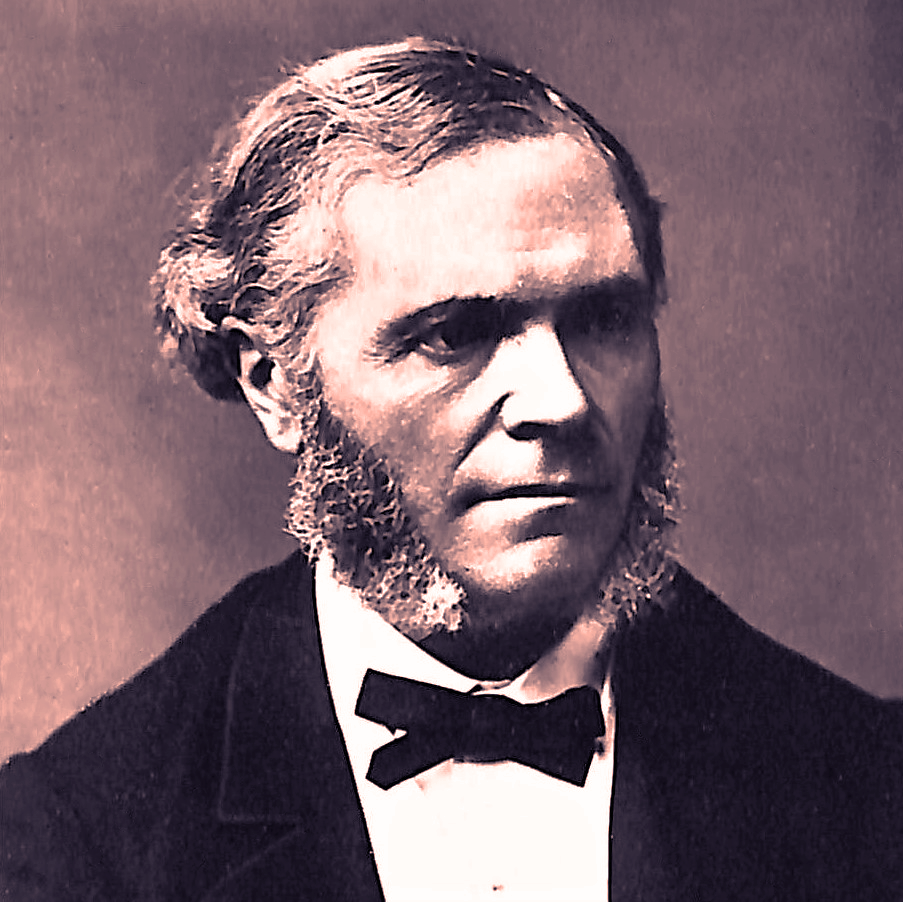

This tutelary figure of French post-Romanticism left a legacy too little known today and a host of fervent disciples including Chausson, D’Indy, Vierne, Ropartz, Tournemire and Bréville.

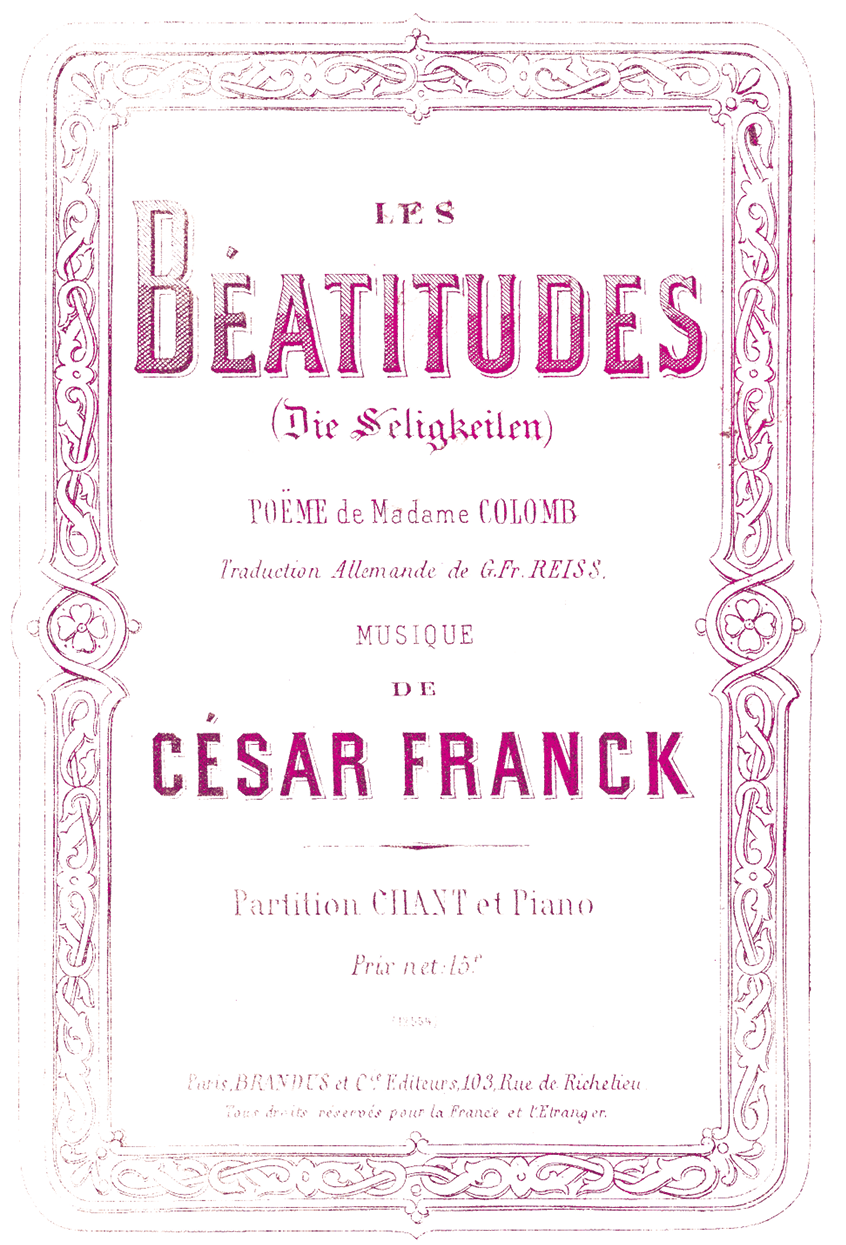

A persistent misconception has left an image of César Franck as an austere organist, torn between mystical devotion and an exclusive interest in taxing instrumental music. This now hackneyed portrait was cultivated by his most faithful pupils, who insisted on his probity, his moral character, his lack of interest in fashion, but also the intellectuality of his creative processes, with a view to sanctifying a French musical movement capable of combating the aesthetics of Wagner and Debussy. Misled by these filters, posterity has retained only a handful of works out of the hundred or so that Franck composed, mainly pieces that seemingly constitute a unique object and give the impression of a genesis devoid of trial and error: ‘the’ Quintet, ‘the’ Sonata, ‘the’ Quartet appear to have no model and no progeny. The same can be said of Les Béatitudes – an oratorio of gigantic proportions – and of the Symphony in D minor, whose cyclic structure was elevated to the status of a compositional blueprint. In celebrating the bicentenary of his birth, with the collaboration of the Liège Royal Philharmonic and the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel, the Palazzetto Bru Zane is determined to present Franck in a new light: the complete songs and duets and the first uncut recording of the opera Hulda will be among the highlights of this resurrection.

A biographical sketch

César Franck was born in Liège in 1822, into a family of music lovers; his father was a bank clerk. It was at the conservatory of his native city that he received his first training, from 1831, in the classes of Jalheau (piano) and Daussoigne (harmony). Four years later, shortly after making his concert debut, he moved to Paris where he studied with Reicha, and then, at the Conservatoire, with Zimmermann (piano), Leborne (counterpoint), Berton (composition) and Benoist (organ). But these promising studies were cut short by his father who, anxious to exploit his son’s virtuoso talents, decided to return to Belgium in 1842. On moving back to France three years later, after breaking with his family, Franck held various positions as teacher and organist. This precarious situation did not end until 1859, when he was appointed resident organist at the church of Sainte-Clotilde. A renowned pedagogue, he was appointed professor of organ at the Conservatoire in 1871 and was one of the founding members of the Société Nationale de Musique, of which he became president in 1886. Although little emphasis has been placed on Franck’s interest in the voice, it features in almost half of his published works, including mélodies and duets with piano, a number of motets, cantatas and oratorios, and four operas whose genesis was as difficult as their creation was problematic: Stradella, Le Valet de ferme, Hulda and Ghiselle. Nor should we neglect his output for piano, in which Franck masterfully distinguishes between the technique of the organ and that of the piano.

The tutelary figure of the French organ

Although trained in Belgium on instruments built in the classical style, Franck followed in the tradition established by the French school of Boëly and Benoist, whose legacy he was to transform. He occupied the position of resident organist at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette (1847), Saint-Jean-Saint-François-du-Marais (1851) and Sainte-Clotilde (1857) successively, and his career as an instrumentalist reached its culmination with the third of these posts, in an organ loft equipped with a brand new instrument by Cavaillé-Coll (1859) that encouraged unlimited creativity. His improvisations at the end of services regularly attracted the most discerning music lovers, while his organ class at the Conservatoire was described as the forum of discussion for modern French music. At both Sainte-Clotilde and the Conservatoire, the instrumentalist gave way to the composer: his improvisations, which gradually took written form, generated a series of masterly works (Trois Chorals, Grande Pièce symphonique, Pièce héroïque), while his organ teaching was subsumed into the more general discourse of a pedagogue whom students came to hear even without being officially enrolled in the class. Throughout his life, Franck published works for his instrument, some of which constitute the most avant-garde portion of his legacy. After him, the French organ school cultivated a harmonic complexity that would be reflected in the works of Gigout, Boëllmann and Widor, leading to the refinements of Vierne and Dupré, and the supreme distortions of Tournemire and Messiaen.

A personal style

Franck’s music is distinguished by stylistic hallmarks that affirm his individuality. First of all, there is the immediacy of harmonic formulas founded on dissonances that colour the tensions typical of late Romanticism. These typically Franckian chords can be found in almost all his output, ranging from the most intimate mélodies to the grandiose organ pieces and the orchestral repertory. He also shows a predilection for constantly recurring rhythmic motifs, especially the syncopated alternation crotchet-minim-crotchet in 4/4 time. Finally, Franck is rightly regarded as the theorist of cyclic form, which consists in reinforcing the unity of a work through the regular reappearance of a founding theme. This theme helps to bestow a coherent structure on the overarching forms, accompanied by secondary themes specific to each movement. These three hallmarks of his music – individual harmony, recognisable melodic outlines and cyclic form – clearly suggest a proximity between Franck and Wagner, and indeed make him the latter’s most obvious French counterpart. However, he stands apart from the German composer both in the genres he covered (Wagner had little interest in pure symphonic discourse, and none at all in chamber or organ music) and in the colouring of his orchestrations: Franck’s music owes a great deal to the mixtures made possible by the stops of the large Cavaillé-Coll organs, and few of his works are free of the thickness and density for which he has sometimes been criticised.

Students or... disciples

Franck’s class was attended by an inconceivable number of young composers, some of whom felt boundless veneration for the man they nicknamed ‘le Père Franck’. In addition to atypical figures for the period, such as the female composers Mel Bonis and Augusta Holmès, the Franckist universe took material shape in a constellation of passionately admiring disciples, among them D’Indy, Ropartz, Vierne, Chausson and Tournemire. The influence of the master is reflected in the work of his emulators, but in a range of complementary styles, since he himself required a composer to seek ‘expression rather than combination’ (D’Indy). The common features of this post-Franckian music are to be found in the density of a discourse featuring constant chromatic shifts, and orchestrations that are the antithesis of the new Symbolist school: his disciples retained Franck’s mixtures of timbres, his use of the low registers of the woodwind, and his preference for deploying the strings in unison rather than in diaphanous divided textures. The adulation of his most fervent students has unfortunately cast a long shadow over the posthumous reputation of their teacher, whom they too often presented as a pure, austere spirit, even a sanctimonious zealot or a mystic. The truth is quite different, for Franck lacked neither humour nor a manifest penchant for sensuality, as may be seen in the passionate impulses displayed by the heroines of his operas Hulda and Ghiselle. When the latter work was left unfinished at the composer’s death, D’Indy, Chausson, Bréville, Rousseau and Coquard swiftly joined forces to complete the orchestration, as a final tribute to their revered role model.

Programme

Torna indietro

Torna indietro  newsletter

newsletter webradio

webradio replay

replay